Lack of bird flu wastewater detection in Central Valley becomes blind spot

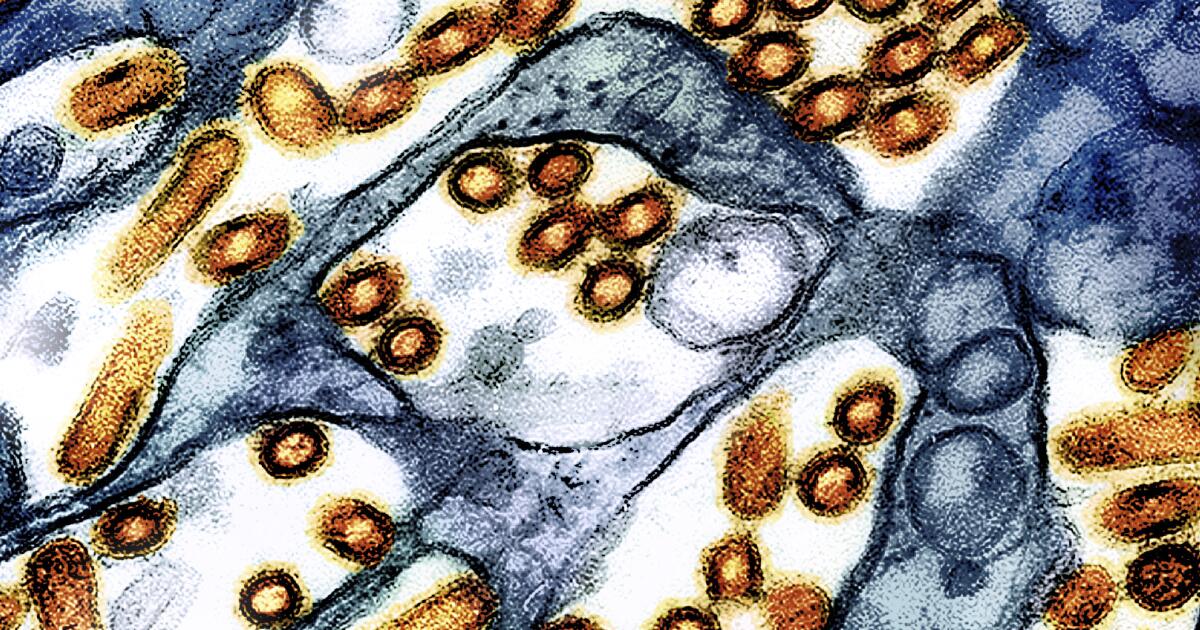

As the H5N1 avian influenza virus continues to ravage California’s dairy herds and commercial poultry flocks, a Central Valley state official is concerned about the region’s lack of wastewater monitoring.

State Sen. Melissa Hurtado (D-Sanger) is frustrated by what she calls gaps in tracking the spread of avian influenza in the Central Valley, where many of the state’s most vulnerable people — dairy and poultry workers — live and Working in the Central Valley.

“If you’re going to track diseases that jump from animals to humans, you need to focus on rural areas like Tulare County, where there are more cattle than people — but there’s no wastewater testing anywhere south of Fresno. test.

As of December 30, 37 people in California have tested positive for the H5N1 virus; all but one are dairy workers. In addition, more than two-thirds of the state’s dairy herds (697 head) are infected, as are 93 commercial or backyard poultry flocks (nearly 22 million birds).

Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency on Dec. 18 after the virus spread from the state’s Central Valley dairy herd to Southern California cows, despite quarantine restrictions designed to stem the spread of the virus.

The virus is also circulating among migratory bird and wildlife populations and has been detected in wastewater treatment sites across the state, including in Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Jose.

However, sampling has been sparse in the Central Valley, where most human cases are reported and the risk is high. In fact, avian flu wastewater sampling is non-existent in some of the most at-risk counties, including Tulare and Kings counties.

Why current tests are not good enough

Wastewater sampling helps public health officials track the spread of the virus. This is a strategy officials are employing to monitor the spread of the coronavirus during the COVID-19 pandemic. In California, officials use wastewater to predict waves of infections and how far the virus will spread among people.

In California, health officials said they were monitoring 78 sites in 36 counties for a range of viruses; all but two sites said they were looking for bird flu.

State officials said in an email to The Times that the state’s Cal-SuWers network is monitoring six locations in the Central Valley, including Kern, Merced, Stanislaus and San Joaquin County.

The most recent sample from Kern County, submitted on Dec. 7, came back positive for the virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

State officials acknowledge this is a major blind spot in the state’s surveillance system, but note they have little control over it.

“Wastewater monitoring at a site…requires utility company participation, which is voluntary,” said Ali Bey, a spokesman for the state agency. “Competing priorities and resource constraints can be reduced [utility’s] Ability to participate.

Tulare and Kings counties have the highest number of human infections in the state, according to data released by each county.

Tulare County Public Health Department spokesperson Laura Flores said the county’s independent wastewater treatment plant has chosen not to participate in the state’s monitoring program. Tulare has 18 reported cases, the most of any county and nearly half of the state total.

Everardo Legaspi, deputy director of the Kings County Public Health Department, did not provide an exact number of human cases reported to the state, telling The Times only that he was aware of “fewer than 10.” . The county has been unable to participate in the state’s wastewater monitoring program since October due to staffing shortages, but the county is working to begin wastewater collection and expand it to other locations in the county, he added.

For months, experts have worried that public health authorities have been slow to respond to the rapidly spreading epidemic, and that public safety has taken a back seat to agricultural interests. Just last month, the USDA began a program to test the nation’s raw milk supply for the virus — about a year after experts believed the virus had spread to cattle and that more than 900 dairy herds and 60 people were infected.

“I do think people are continuing to reduce the impact of this outbreak and this virus,” said Rick Bright, a virologist and former head of the U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority. “Our government officials did not conduct the thorough investigation that they should have done.”

Even after the USDA announced its new bulk milk testing program, the initial rollout was limited to 13 states; many states, including California, Colorado and Michigan, are already testing their milk.

The incoming Trump administration has threatened to withdraw the United States from the World Health Organization, a move that would further turn a blind eye to the movement of the virus in the United States and the rest of the world. That’s despite the Biden administration announcing Thursday that it will spend an additional $306 million to prevent possible outbreaks of avian flu in humans — funds that will be distributed before he leaves office later this month.

“I don’t think the right questions are being asked to understand this bird flu,” Hurtado said. “A lot of that is due to a lack of guidance from the federal government.”

What we can learn from avian influenza surveillance, if we do it right

To be sure, the discovery of bird flu in wastewater does not mean the virus is breaking out in humans.

Unlike COVID-19, mpox or seasonal influenza (which is found in wastewater showing human infection), positive samples for avian influenza can come from a variety of sources, including pasteurized milk. This is because the method used to sample avian influenza in wastewater looks for viral markers rather than the entire virus.

This means the test may pick up inactivated fragments of the virus, like those found in commercial pasteurized milk.

“I don’t think we really know what this means,” said Richard Webby, director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Research on the Ecology of Animal and Avian Influenza. “How much milk is poured down the drain in urban areas? We know the levels in supermarket milk can be high. I actually don’t know what supermarkets do with expired milk.

It could also come from raw milk or raw meat. Even the waste products of wild birds and mammals, in which the virus is currently circulating.

Since the outbreak began, California officials have found the virus in wild birds such as rock pigeons, white-faced ibises and turkey vultures, as well as wild mammals such as mountain lions, raccoons and skunks.

In addition, inactivated viruses may be shed in people’s feces, said Alexandra Boehm, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford University and principal investigator and program director of WastewaterSCAN.

The struggle to improve the system

Whatever the samples show, they provide evidence that the virus is circulating somewhere in the environment.

Bright said health and water officials in some parts of the state are deliberately not looking for the virus, another example of the government’s failure to control the disease and track its spread.

“The virus is evolving rapidly… Without full participation in surveillance and testing programs, coupled with adequate and timely transparency, we will always be behind the virus,” Bright said. “Without federal, state, local and Without adequate collaboration and cooperation at the community level, our ability to address this issue will be hampered.”

For Hurtado, the situation is also personal.

She said her father and niece, who live in the Central Valley, had symptoms of bird flu earlier this year, but there were no tests to confirm her suspicions.

Her father contracted a virus that nearly killed him and left him with severe muscle and body pain, symptoms of bird flu. Her 7-year-old niece, who lives in Sanger, a town with a large poultry processing plant, recently developed a rare autoimmune reaction to a virus. Her eyes were red and swollen, a symptom of the H5N1 virus. Her doctors didn’t know what triggered the reaction.

She said neither man had been tested for bird flu despite showing symptoms, but she suspected they were infected. Dairy farmers, workers and family members also told The Times they believe the numbers reported by the state may be an undercount because some workers may not report being sick for fear of losing their jobs.

“I have no science or information to back this up, but my heart tells me that both my father and my niece have bird flu,” she said. “Both were seriously ill from an unknown virus.”

Her personal experience prompted her to urge governments to seek answers to track the spread of the virus. She has asked the state health department about the lack of testing in the Central Valley, but said she has not yet received a clear response.

Hurtado also pushed for increased testing in high-risk communities. While there is some testing of high-risk individuals, including dairy and poultry workers, the state has not provided a comprehensive approach to testing agriculturally intensive communities.

Hurtado, whose district includes a large swath of the Central Valley, said she intends to introduce legislation that would expand the state’s wastewater monitoring program to include sites in rural underserved and high-risk communities. The legislation would also establish criteria for identifying high-priority sites based on health risks, population density and socioeconomic factors.

Hurtado worries about communities like her hometown of Sanger. There was a poultry processing plant, one of the city and county’s largest employers, that was hit hard by avian influenza.

Since the end of October, more than a dozen commercial poultry farms in Fresno County have been hit by the virus, resulting in the culling of more than 1.5 million birds.

She’s heard stories of workers losing time on the job because animals got sick and poultry farms were cut altogether. Affected by the epidemic, egg prices have also increased.

“I think we could have done more earlier,” she said. “But we’re here and we have to be able to improve where we failed.”